Stem post models as learning and identity construction devices

This short paper was written as an assignment required for the PhD course “The Social Context of Technology“, organized by the Dialogues with the Past – Nordic Graduate School in Archaeology. Although not directly connected to my research project, it touches relevant topics such as “community of practice” and the embeddedness of technological practices within a society. Furthermore, it aims to underline how boatbuilding technology was a central element in everyday life in norse settlements of the late Iron Age and early medieval period.

This paper aims to revisit a specific class of maritime material culture from medieval Norse settlements under the lens of Situated Learning and Community of Practice, and by bringing forward a new discussion and interpretation of these objects also with an example from real-world observation, sort to say.

The objects discussed here are miniaturised versions of stems of boats and ships, usually classified as playthings but never explored beyond this broad definition. Although in short, this paper puts forward the idea that these pieces of maritime material culture are not merely toys made by children but informal learning and identity construction devices.

Without doubts, any material culture encapsulates the environmental and technological constraints and the economic, social and political organisations of the people producing it (Sillar and Tite 2000, p. 4). At the same time, as proposed by Prown (1982, p. 2), objects made or modified by man reflect, consciously or unconsciously, directly or indirectly, the beliefs of the individuals who made or owned them as the beliefs of their societies. Beliefs not just intended in the strict meaning of the term but also as ideas and emotions (Dant 1999, p. 3).

Under this perspective, craft learning during childhood should not be exclusively conceived as the simple transmission of a series of technical knowledge and internalised psychomotor practices but also as a process of social construction which originates in the educational modes rooted in the attitude and structures of each community (Calvo Trias et al. 2015, p. 88). This social practice of technological knowledge transmission constitutes, in turn, a critical factor in children’s socialisation, as well as the configuration of a specific way of perceiving and understanding the world.

Analysing the social context of craft production has been a growing theme in the literature about children and craft production that extends beyond methods for identifying children archaeologically (e.g., Crown 2001, 2014, Smith 2005, Calvo Trias et al. 2015). However, little focus has been given to material culture produced by children outside craft production settings. This paper proposes that even playthings crafted by children, not aimed directly at craft production, can still reveal pieces of information about their social context by applying concepts such as Situated Learning and Legitimate Peripheral Participation (discussed in the next section).

Approaching the concept of technology as inherently social acknowledges that craft and production consist of complex networks of actions, actants, and interactions (Wolfe 2019, p. 53). Thus, any material culture produced by any member of any society is a network of vital nodes indispensable to the final configuration, stemming from specific local, social, and environmental contexts. At the same time, to craft is to create with a specific form, objective, or goal already in mind. Costin (1998, p. 4) states:

“Crafting is a quintessential human activity, involving premeditative thought and deliberate, design-directed action”

In this sense, craftspersons are active and participatory agents in the “action” of symbols (Hodder 1982) and the “materialisation” of ideology (DeMarrais et al. 1996). They can actively create or capture social context and meaning and communicate it nonverbally in the objects they create (Costin 1998, p. 5).

The objects discussed here are miniaturised versions of stems of boats and ships, usually classified as playthings but never explored beyond this broad definition. Although in short, this paper puts forward the idea that these pieces of maritime material culture are not merely toys made by children but informal learning and identity construction devices.

Playthings, children, and situated learning

In an archaeological context, toys can provide a way to recognise the remains of children’s behaviour, interaction and socialisation (Baxter 2005, p. 41). As with any material culture, children’s playthings are imbued with meanings that depend on their social context. Meanings are not embedded in the object but are assigned or attributed by individuals and their cultural contexts (Hodder 1989, Beaudry et al. 1991, p. 157). Thus, toys can assume contradictory meanings between adults and children.

Utilising toys as portals to access children and childhood in the past presents its own set of difficulties, as it can lead to the child’s separation from what is perceived as the more ‘serious’ adult world (Lillehammer 1989, pp. 98–100). However, approaching children’s toys as meaningful tools within the socialisation process provides an opportunity to study Situated Learning and the acquisition of technical competence (Baxter 2005, p. 12), especially if children make the toys.

Situated Learning Theory and community of practice

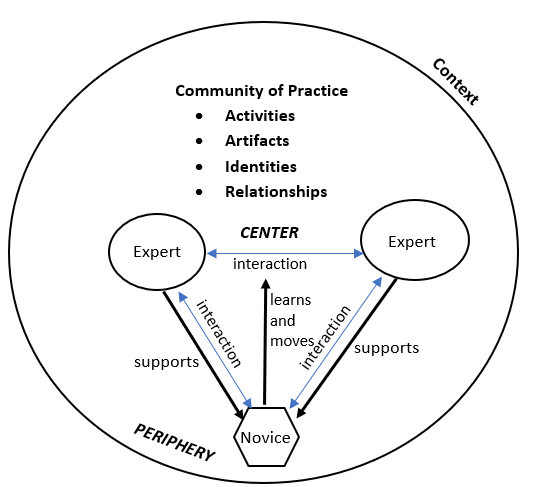

Situated Learning (SL) theory (Lave and Wenger 1991) places childhood play and learning as elements in the socialisation process. SL theory suggests that learning develops through social interaction and not as a unique process in situations designed explicitly for instructions. Instead, learning is embedded in both social and physical contexts.

Situated Learning takes place through participation in authentic activities, creating a notion of “learning in situ” in a process by which ”newcomers” to a community of practice gradually become participating members by “learning by doing”. (Lave and Wenger 1991 pp. 29, 113). Thus learning is an inseparable aspect of social practice that occurs at the juncture of everyday interactions. According to Lave and Wenger (1991, p.53), activities, tasks, functions, and understandings do not exist in isolation but are a part of broader systems of relations that have meaning. To cite Lave and Wenger (1991, p.54): “it is important to consider how shared cultural systems of meaning and political-economic structuring are interrelated, in general, as they help to co-constitute learning in communities of practice”.

The concept of community of practice (Lave and Wenger 1991, Wenger 1998) describes a group with a shared history of learning engaged in a joint enterprise (Wenger 1998, pp. 71–72). Fundamental to this concept is the idea of learning as social participation, which shapes identity. Furthermore, Lave and Wenger (1991, p.14) also introduced the concept of Legitimate Peripheral Participation as “the particular mode of engagement of a learner who participates in the actual practice of an expert, but only to a limited degree and with limited responsibility for the ultimate product as a whole.”. The learning process begins by approaching the least dangerous and complex tasks on the periphery of crafts as someone engages in practice (Lave and Wenger 1991, p. 72).

Using the notion of SL while examining and analysing archaeological child-related material culture may help reveal how children were perceived and included in past societies and how they perceived their societies. Situated Learning is beneficial to study child-related objects, which are generally considered to represent “imitative behaviour” because they mirror adult tools and adult “world” objects in miniature and, therefore, are likely to represent a learning and skill acquisition experience.

Children as producers of material culture

Object identification and categorisation as toys in the archaeological records are often based on the small size, crude manufacture, or similarity to items used as playthings in modern cultures (Baxter 2005, p. 46). Fundamental to identifying children-made objects has been the issue of size and craftsmanship quality (Menon and Varma 2010, p. 86). Indeed small, poorly drawn, sculpted, or shaped figures in the archaeological record are features associated with being used and created by children (Lewis 2007, p. 9). Miniaturisation is one of the ways a plaything can be created to represent artefacts used or made by adults. Such objects allow children to mimic and practice adult social roles and physical tasks, serving as devices in the socialisation of children (Baxter 2005, p.47).

If modern western cultures tend to marginalise the role of children as producers of material culture, ethnoarchaeological studies (Menon and Varma 2010, Crown 2014, Calvo Trias et al. 2015) have shown that children have long been integral to production communities in various cultures. For children to become competent producers of material culture and part of a community of producers, they must be socialised in the theory and tradition of the craft and must learn the technical skill necessary for production (Baxter 2005, p. 50).

Ethnoarchaeological literature on children and pottery production is rich in examples that could be applied to other crafts. For instance, Calvo Trias et al. (2015), in their study on children’s learning in Kusasi ceramic production, showed how some children play with clay and make objects which reproduce, symbolise and imitate activities carried out by adults. The game becomes an activity where children, in an unguided way and through their unprompted trials and experiments, follow imitative processes which incorporate not only the observation of adult technological practices but also mental duplication as well as gestural and technical memorisation processes (Calvo Trias et al. 2015, p. 104). In this context, toy fabrication becomes a kind of ‘proto-learning’, as its execution would be impossible without acquiring specific structured technical knowledge previously assimilated, recorded and imitated (Calvo Trias et al. 2015, p. 104).

Furthermore, Menon and Varma (2010) highlighted how small-sized ceramic vessels crafted by children showed a bit of both high-quality and low-quality craftsmanship, suggesting a gradual learning process from miniature to small to large vessels. In ancient Indor Khera, figurines and miniature vessels were toys and steps to initiate children into technical processes working with clay (Menon and Varma 2010, p. 88).

The stem post models

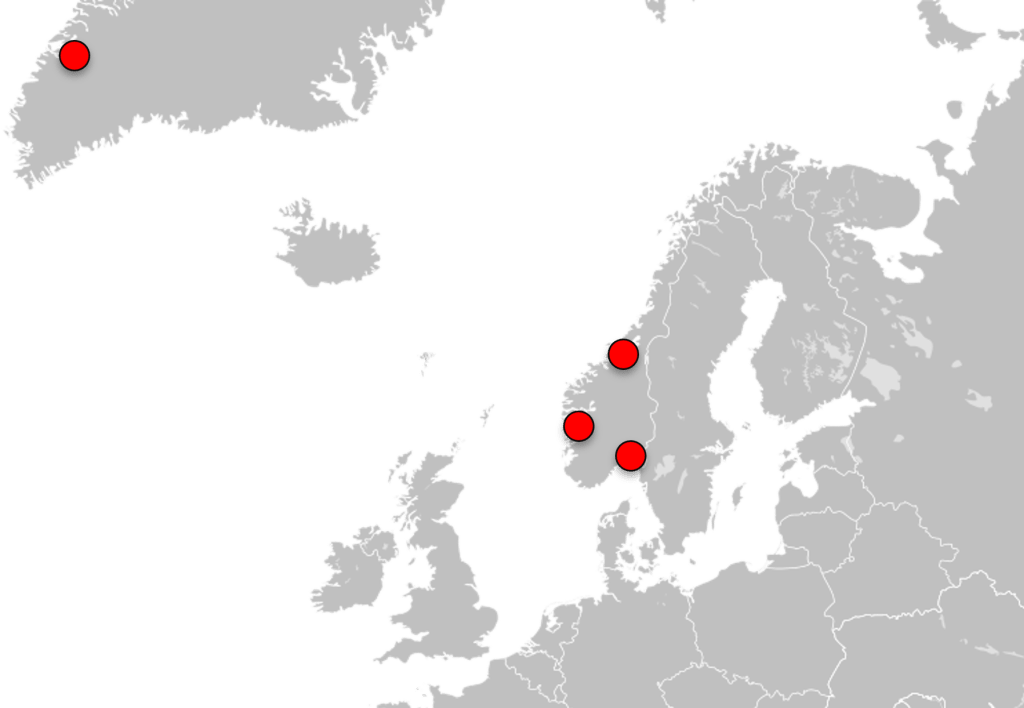

The material discussed here is classified in archaeological literature as playthings, representing miniaturised curved stem posts made of wood of boats and ships. As far as the published material can tell, these objects have only been found in Norway and Greenland.

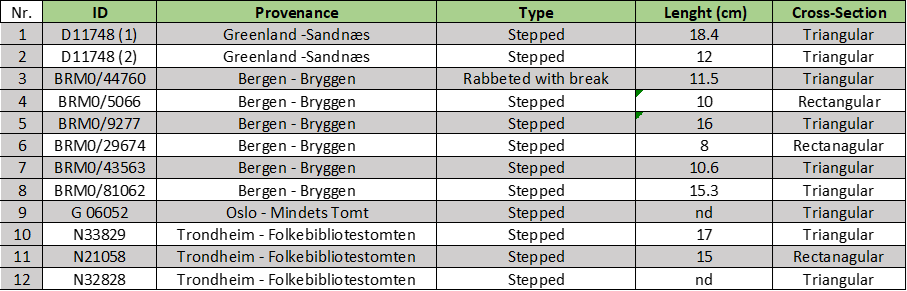

The compiled short catalogue only considers materials undoubtedly identified as stem models and with enough information for their description (Table 1). None of the materials is closely dated as the site where they originate from were long-lived, but they can generally be framed in the Late Viking age and Early Medieval period.

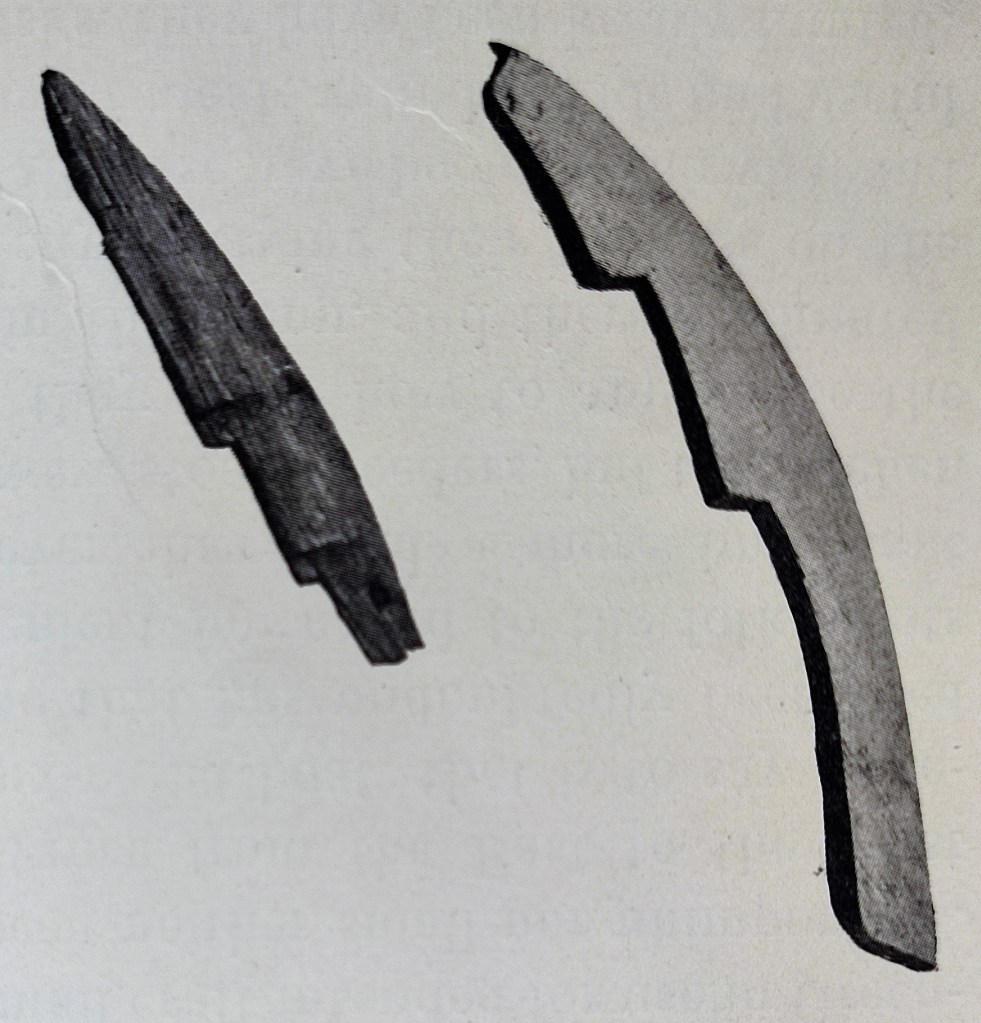

Greenland

The stem models nr.1 and nr.2 (were found in Sandnæs, the most significant Norse farmstead in the Western Settlement of medieval Greenland, during archaeological investigations of the settlement and its neighbouring farms in 1930-32 (Roussell 1936, p. 100). Both models were found in the building identified as a house (Building 4, Ruin Group 51), in the northern part of the “pantry” room (Roussell 1936, p. 170). The stems represent a stepped type of stem, of which examples are well-known from the Viking age. In both models, notches are visible for the scarfing of planks at each step. However, nothing indicates that actual planks were ever attached. The stem nr.2, not fully preserved, was connected at the bottom to another piece through a scarf and a small nail.

Other artefacts from the same house were also recovered, classifiable as playthings (Roussell 1936, pp. 117–130), such as a wooden spinning top, a miniature cooking pot of soapstone, and several roughly carved human and animal figurines of wood and bone.

Bergen

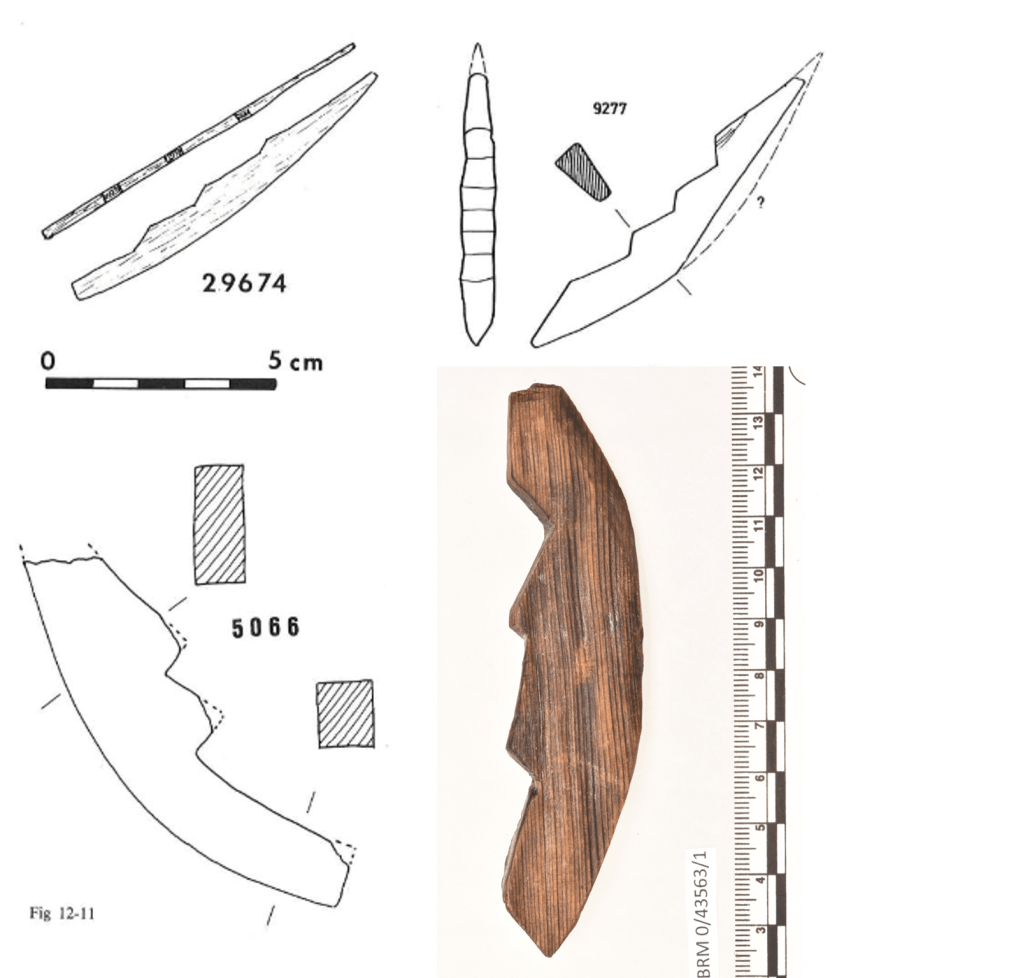

Models nr.3 to nr.8 originate from the archaeological excavations at Bryggen, the old Hanseatic Wharf in Bergen, in 1955-68. Christensen (1985, pp. 157–169) and Mygland (2007, pp. 36–38) analysed and catalogued these artefacts and classified them as probable toys.

As for most of the objects recovered from Bryggen, these models originated from man-made fills and cannot easily be linked to buildings and other structures, while they can be chronologically framed between AD 1170 and 1332 (Christensen 1985, p.160).

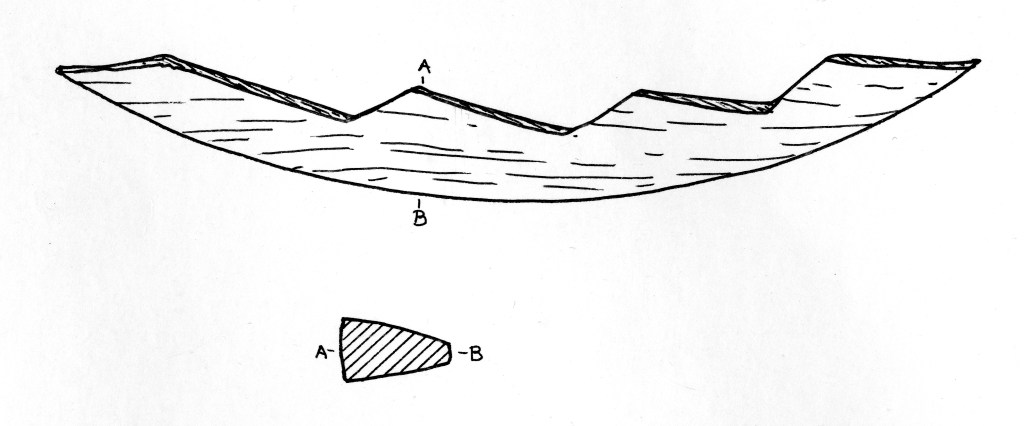

Except for nr.3, the stem models are stepped and show different craftsmanship qualities. Nr.5 to Nr.7 appear roughly fashioned while nr.8 is carefully shaped and presents engraved stripes, a common feature of several ships from the Viking Period and the Middle Ages (Christensen 1985, p. 158). Furthermore, the models show no fastenings or other indications of being part of model vessels (Christensen 1985, p. 159).

From the Bryggen excavation, which covered an area of around 5700 sq. metres, originated 1,763 child-related artefacts (Mygland 2007, p. 82), of which 27 boat models and other 27 maritime-related toys or models (Mygland 2007, p. 36-37).

Besides the stem post models discussed here, miniaturised models of stem-tops, masts, parrels, and bailers have been found. These objects might have belonged to larger boat models, but the stem-tops might have been part remains of wooden candle-holders of the same type as the wrought iron ones from Dale and Urnes (Christiansen 1985, p. 159)

Oslo

The stem model nr.9 was unearthed during the excavations in 1971-72 in “Mindset Tomt” in Gamlebyen, the oldest urban area within Oslo. At the moment, it is the only known example from Oslo. Like Bryggen in Bergen, the site consists of several temporal (28) and functional phases, such as fills, habitations and workshops, dating between AD 1000 and 1624 (Lidén 1977).

This model is relatively simple and represents a curved stepped stem post, with no decorations or notches from the planking. Again, like the cases above, it shows no indications of being part of a ship or boat model but is still classified as a plaything (Weber 1990, pp. 162-163).

From the same site, between all the layers, several toys and maritime-related toys were found, such as miniature weapons and tools, wooden spinning-tops and also 16 boat models (Weber 1990, pp. 162–168).

Trondheim

Similarly to the stem models from Bergen and Oslo, the models nr.10 to nr.12 originate from a highly stratified medieval urban context in Trondheim, specifically from the archaeological excavation conducted in 1974-76 at the “Folkebibliotekstomten”, with 12 phases dating between AD 900 and 1600 (Christophersen et al. 1994).

The models can be chronologically framed between AD 1050 and 1325, while their context of provenance seems to relate to the domestic sphere of the buildings (Fahre 1998, pp. 92–96).

All three models are reproductions of stepped stems, and nr.10 and nr.11 have carved decorative lines. Stem model nr.10 is the most carefully shaped. Again, like all the other contexts presented here, several other playthings were found at the site, from miniature weapons to utensils, from figurines to boat models.

A summary

Besides one stem model in the list, the stepped type seems to be the typical representation. They are accurate miniatures of boats and ships stems known from full-sized counterparts from archaeological materials from the Viking Age to the Early Medieval period (e.g. Christensen 1959, Gøthche 1995).

Although the materials from Bergen and Oslo can not be linked to any specific contexts of origin, the models from Trondheim and Greenland seem to be directly connected to domestic life rather than workshops or production sites. Their dimensions vary but remain within the range of an object that can be easily held with one hand. The quality of their craftsmanship is highly variable, from roughly carved-out ones to nicely finished with incised lines. Furthermore, 11 out of 12 models have a triangular cross-section, another realistic feature of full-sized stems, showing that care is given to the three-dimensionality of these objects. None of them has been used in constructing a large model; thus, their creation seems to be an end in itself.

Toys, tools or more?

If these objects are toys and were shaped to be only boat stem posts, naturally, it raises the question of how these stems were played with. Perhaps they had other functions, or instead, the production stage was a significant part of the game.

Maritime archaeologist Arne Emil Christensen (1985, p. 160) considers the discussed artefacts likely to be playthings, but he also proposes other interpretations. Although he considered it improbable, he suggests shipbuilders might have used the stem models as a template to demonstrate the shape to potential clients. On the other hand, Christensen (1985, p. 160) is keener to interpret these artefacts as the result of perhaps adults’ aimless whittling or idle carvers who have chosen to depict the most visible detail of a ship, the bold curves of the stem. Another maritime archaeologist, Ole Crumlin-Pedersen (1997, p. 172), suggested that the models could have served as miniature scale moulds for stems to be taken along into the woods or to the driftwood on the coast when the boat builder began the search for crooked timbers for the stem of a new vessel. Instead, Mygland (2007, p. 36-37) is keen to interpret the stem models as playthings due to their proximity to other children’s related objects.

Scale models as templates are not a foreign concept in boatbuilding, but they had no place in traditional clinker-building, to which these stem models belong. Full-sized moulds have only recently sipped into clinker boatbuilding, resulting from probable cross-contamination from other building traditions (Christensen 1972, pp. 252–256). A scale model as a template is closer in concept to a drawing or written instructions, typical of our education system dominated by “the verbal principal” (Christensen 1972, p. 236). Instead, set rules of thumb seemed to have been the norm from the Viking Age onwards (Crumlin-Pedersen 2004, p. 50). A set of proportions and rules of thumb allow a more straightforward but effective scaling method leaving room for variations and a more straightforward transmission method to the next generations.

If the explanation of stem post models as devices in the construction of an actual ship seems highly improbable, perhaps it is helpful to look at other maritime toys such as boat models. Ravn (2012, 2017) concludes that boat models from the Viking Age might be understood as tools in a maritime community of practice, which allowed children to make first contact with seamanship and perceptions of life at sea through play. Similarly, applying the concepts of Situated Learning and Legitimate Peripheral Participation, stem post models can be interpreted as tools for learning through play, which allowed children or young individuals who made them engaging in a game of imitation of a shipbuilding practice.

Learning the shape? An example from direct observation in a traditional boatyard.

In describing the building of the Roar Ege, a copy of Skuldelev 3, Vadstrup (Crumlin-Pedersen et al. 1997, p. 86) notes that the shaping and carving of the stepped stem posts were complex and time-consuming and achieved using several tools such as planes, axes and scrapers.

At the production stage, miniaturisation requires different choices in technical practices. These alterations in practice are reflected in the operational sequences, or chaîne opératoire, involved in producing miniatures and their normal-sized counterparts (Kohring 2011, p. 32). By changing dimensionality, the techniques and tools required to produce an object, such as a wooden stem post, differ from their life-sized counterparts. However, it will still allow familiarising with materials, other tools, and above all, the object’s shape.

Perhaps a direct observation from a traditional boatyard might be helpful here. Engøyholmen[2] Coastal Culture centre in Stavanger (Norway) runs a wide range of activities related to traditional crafts. Above all, they build and maintain traditional boats. Recently the centre has been tasked to build not a replica but a boat inspired by the Gokstad færing, the smallest boat found in the Gokstad mound from the early Viking Age (Christensen 1959). In any case, they opted to adopt and replicate the stem posts from the original find, which are of the stepped type. Although the boatbuilder in charge has over 25 years of experience, this became a more challenging task than thought due to the complex geometry and lack of previous experience in carving such stem (personal communication). During a visit to Engøyholmen, the topic of miniature stem posts came up, and I proposed that making these miniatures might have helped to familiarise with such a complex shape. Master boatbuilder Hannes Carsten Reuter became intrigued by the idea and began working on a model on his porch the same evening, using a draw knife. A few days later, he reached out to communicate how carving such a model helped not only to familiarise himself with the shape but also how to tackle it with the proper tools. It must be noted, that compared to the stems under study, the model made by this experience boatbuilder shows a higher degree of complexity in form and shaping. This could be easily explained by the fact he is a master practitioner with years of experience in woodworking rather than a novice or peripheral participant.

This example might shed light on how shaping a model of a stem can be seen in the context of informal learning. It can be seen as an imitation game and step to initiate children or young individuals into a technical process that helps familiarise them with the object’s morphology and create a mental pattern of its three-dimensionality.

Ship Stems and the Stem-smith: shaping the social persona?

Vadstrup (Crumlin-Pedersen et al. 1997, p. 86) described the stem as the “face” of the ship, the most prominent and visible feature. Indeed, elegant stems are a notable characteristic of Viking Age and Early Medieval Scandinavian ships and are often described in great detail in the skaldic stanzas (Jesch 2001, p. 144). In the skaldic examples, the word stafn (stem) is often used in the extended meaning of ship.

Together with the stanzas, archaeological finds of stem posts indicate that a great deal of effort and craftsmanship was devoted to the dressing and carving of this ship part (Shetelig 1917, p. 290, Crumlin-Pedersen and Olsen 2002, p. 201,273, Ravn 2020, p. 100). Christensen (1985, p. 207) stresses the importance of the correct cutting of the stem and postulates both that “the stem was a prestigious object and that good stem-cutters were highly regarded by others”. Thus, the term stem-smith was not unexpectedly used to describe a skilled artisan with a leading role in boatbuilding (Ravn 2020, p. 100).

Stem-smiths were so highly regarded and proud figures that in a case described in the Icelandic saga Heimskringla, written around 1235 by Snorri Sturluson (Sandvik n.d., p. 10), one even defies his king to prove his great boatbuilding skills (Snorri Sturluson 1967, p. 111). Hence, in this context, carving a model of a stem assumes an additional meaning, perhaps of social ambition and aspiration.

Conclusion

The discussion here has tried to give a new understanding of these pieces of maritime material culture. Their context of provenance suggests that stem post models were playthings originating from domestic contexts, or at least not directly connected with a production site. Furthermore, it seems more reasonable to shift the focus on how and why these objects were produced rather than just label them as merely toys. Indeed, the “play” aspect is not to be searched the object in itself but rather the production process and what the objects represent. These stem post models can be seen as objects of Situated Learning made by children as peripheral participants in a community of practice and, at the same time, as a reification of ambition and social persona. Ravn (2017, p. 133) states:

“The transmission of tradition in a community of practice begins with the youngest of the marginal participants, the children.”

Thus, children’s play is an integral component in the labour organisation as well as the creation and transmission of knowledge and skills within the community of practice and society (Ravn 2017, p. 133). At the same time, it is also a socialisation device that helps to shape identities (Baxter 2005, p. 31)

While children as active agents are visualised in archaeological studies of craft production across the globe, more remains to be done regarding the Norse realities. This brief discussion has tried to locate children as “newcomers” within a community of practice and show them as active producers of material culture and identity. At the moment this paper is going trough a re-editing and deepening of some the concepts touched here. For example, it is interesting to notice that the production of these stems seems tightly related to Norwegian norse settlements and found nowhere else in Scandinavia.

References

- Baxter, J.E., 2005. The Archaeology of Childhood: Children, Gender, and Material Culture. Rowman Altamira.

- Beaudry, M.C., Cook, L.J., and Mrozowski, S.A., 1991. Artifacts and active voices: Material culture as social discourse. In: R. McGuire and R. Paynter, eds. The Arcaheology of Inequality. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 150–91.

- Calvo Trias, M., Garcia Rossello, J., Javaloyas Molina, D., and Albero Santacreu, D., 2015. Playing with mud? An ethnoarchaeological approach to children’s learning in Kusasi ceramic production. In: M. Sánchez Romero, E. Alarcón García, and G. Aranda Jiménez, eds. Children, identity and space. Oxford: Oxbow, 88–104.

- Christensen, A.E., 1959. Færingen fra Gokstad. Viking, XXIII, 57–69.

- Christensen, A.E., 1972. Boatbuilding Tools and the Process of Learning. In: O. Hasslof, H. Henningsen, and A.E. Christensen, eds. Ships and shipyards, sailors and fishermen. Copenhagen: Copenhagen University Press, for the Scandinavian Maritime History Working Group.

- Christensen, A.E., 1985. Boat Finds from Bryggen. In: The Archaeological Excavations at Bryggen. Universitetforlaget AS, 47–272.

- Christophersen, A., Nordeide, S.W., and Riksantikvaren, 1994. Kaupangen ved Nidelva: 1000 års byhistorie belyst gjennom de arkeologiske undersøkelsene på folkebibliotekstomten i Trondheim 1973-1985. [D. 1. Kaupangen ved Nidelva. Oslo: Oslo] : Riksantikvaren, 1994.

- Costin, C.L., 1998. Introduction: Craft and Social Identity. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, 8 (1).

- Crown, P., 2001. Learning to Make Pottery in the Prehispanic American Southwest. Journal of Anthropological Research, 57, 451–469.

- Crown, PL, 2014. The Archaeology of Crafts Learning: Becoming a Potter in the Puebloan Southwest. Annual Review of Anthropology, 43 (1), 71–88.

- Crumlin-Pedersen, O., 1997. Viking-age Ships and Shipbuilding in Hedeby/Haithabu and Schleswig. Archäologisches Landesmuseum der Christian-Albrechts-Universität.

- Crumlin-Pedersen, O., 2004. Nordic Clinker Construction. In: FM Hocker and C.A. Ward, eds. The Philosophy of Shipbuilding: Conceptual Approaches to the Study of Wooden Ships. Texas A&M University Press, 37–63.

- Crumlin-Pedersen, O. and Olsen, O., 2002. The Skuldelev Ships I: Topography, Archaeology, History, Conservation and Display. Viking Ship Museum.

- Crumlin-Pedersen, O., Vinner, M., Andersen, E., and Vadstrup, S., 1997. Roar Ege: skuldelev 3 skibet som arkaeologisk eksperiment. Vikingeskibshallen.

- Dant, T., 1999. Material culture in the social world : values, activities, lifestyles. Buckingham ; Philadelphia : Open University Press.

- DeMarrais, E., Castillo, L.J., and Earle, T., 1996. Ideology, Materialization, and Power Strategies. Current Anthropology, 37 (1), 15–31.

- Fahre, L., 1998. Livet leker! –en studie av lekematerialet fra folkebibliotekstomten i Trondheim som er datert til perioden 970–1500. Hovedfagsoppgave i nordisk arkeologi. Universitet i Oslo, Oslo.

- Gøthche, M., 1995. Båden fra Gislinge. In: Nationalmuseets arbejdsmark. Copenhagen: Foreningen Nationalmuseets Venner.

- Hodder, I., 1982. Symbols in Action: Ethnoarchaeological Studies of Material Culture. Cambridge University Press.

- Hodder, I., 1989. The Meanings of Things: Material Culture and Symbolic Expression. Routledge.

- Jesch, J., 2001. Ships and Men in the Late Viking Age: The Vocabulary of Runic Inscriptions and Skaldic Verse. Boydell & Brewer.

- Kohring, S., 2011. Bodily skill and the aesthetics of miniaturisation. Pallas, (86), 31–50.

- Lave, J. and Wenger, E., 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Lewis, M.E., 2007. The Bioarchaeology of Children: Perspectives from Biological and Forensic Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lidén, H.-E., 1977. De Arkeologiske utgravninger i Gamlebyen, Oslo. 1: Feltet ‘Mindets tomt’ : stratigrafi, topografi, daterende funngrupper. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Lillehammer, G., 1989. A child is born. The child’s world in an archaeological perspective. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 22 (2), 89–105.

- Menon, J. and Varma, S., 2010. Children Playing and Learning: Crafting Ceramics in Ancient Indor Khera. Asian Perspectives, 49 (1), 85–109.

- Mygland, S.S., 2007. Children in Medieval Bergen: an archaeological analysis of child-related artefacts. Bergen: Fagbokforl.

- Prown, J.D., 1982. Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method. Winterthur Portfolio, 17 (1), 1–19.

- Ravn, M., 2012. Maritim læring i vikingetiden – Om praksisfællesskabets marginale deltagere. Kuml, 61 (61), 137–149.

- Ravn, M., 2017. Children in maritime communities of practice. In: J. Gawronski, A. van Holk, and J. Schokkenbroek, eds. Ships And Maritime Landscapes: Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Symposium on Boat and Ship Archaeology, Amsterdam 2012. Presented at the ISBSA, Barkhuis.

- Ravn, M., 2020. Early Medieval Nordic Boatbuilding Technology: Reflections on How to Investigate Negotiation Processes in Past Communities of Practice. Lund Archaeological Review, 24–25 (2018–2019), 97–110.

- Roussell, A., 1936. Sandnes and the neighbouring farms. Reitzel.

- Sandvik, G., n.d. Introduction. In: From the Sagas of the Norse Kings. Oslo & Stavanger.

- Shetelig, H., 1917. Skibet. In: Osebergfundet.

- Sillar, B. and Tite, M.S., 2000. The Challenge Of ‘Technological Choices’ For Material Science Approaches In Archaeology. Archaeometry, 42 (1), 2–20.

- Smith, P.E., 2005. Children and Ceramic Innovation: A Study in the Archaeology of Children. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, 15 (1), 65–76.

- Weber, B., 1990. Tregjenstander. De Arkeologiske utgravninger i Gamlebyen, Oslo. 7-8 1: Dagliglivets gjenstander. Øvre Ervik: Øvre Ervik : Alvheim & Eide, 1990-1991.

- Wenger, E., 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Wolfe, U.I.Z.-M., 2019. Grasping at Threads: A Discussion on Archaeology and Craft. In: C. Burke and S.M. Spencer-Wood, eds. Crafting in the World. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 51–73.