Some notes….

As already introduced, my research focuses on using ships and boats found from bogs and graves as source material for the study of shipbuilding during the Late Iron Age in W-Norway. To quote Crumlin-Pedersen (98), finds from “different contexts tend to produce different types of ships and boats”. Therefore, analysing finds from various contexts will produce a more representative understanding of shipbuilding in the region.

Boats and ships from “grave” contexts are pretty straightforward, as they are intentionally buried as the tomb or part of the grave goods. Therefore, they entered the archaeological records as a result of funeral rites. On the other hand, remains found in bogs require some explaining.

In the 1929 publication dedicated to the excavation results and study of the Kvalsund finds, Shetelig and Johannessen also put together a comprehensive catalogue of nautical timbers found in bogs in Norway. According to their research (Shetelig and Johannessen 34–56), boat/ship finds and nautical woods found in wetlands have entered the archaeological records either as:

- ritual depositions

- discarded or wrecked vessels in marshy areas

- intentionally deposited wooden blanks employed in ship and boatbuilding

Ritual deposition

Wetland deposits in Scandinavia date from the Mesolithic period to the Middle Ages. They include a variety of objects, from animal bones to earthware vessels, from weaponry to boats.

“We cannot get away from the fact that the depositions in the bogs were connected with the ritual/religious sphere.”

Kaul 19

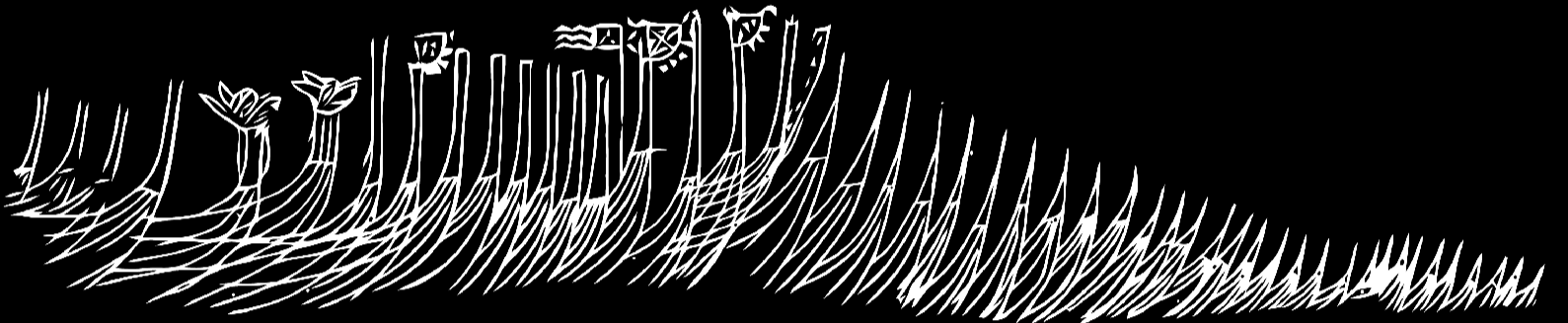

The two most iconic examples of ritualistic boat deposition in wetlands originate from Denmark. The Hjortspring boat, a large canoe from the Scandinavian Pre-Roman Iron Age, and the Nydam boat, a 23m long vessel dated to 310–320 AD. It is generally agreed that they were deliberately buried in a bog as a war offering. In the case of the Nydam boat also intentionally broken into pieces.

The most famous Norwegian case is one of the so-called Kvalsundfunnet from Nerlandsøya in the municipality of Herøy. During the summer of 1920, Johannes J. Kvalsund and his son Jacob uncovered some wooden elements while cutting peat on their farm. The archaeologist Haakon Shetelig from the Bergen Museum immediately travelled to Kvalsund and started excavating with his assistants. The site consisted of scattered and mixed remains of a larger (ca 18 m in length) vessel and a smaller (ca 9.5m in length). All evidence indicated that the boats were intentionally destroyed and put in a peat bog as a ritual offering. In 2020, the Kvalsund ship and boat were dated through dendrochronology, firmly placing their construction in 780–800 AD (Nordeide et al.).

The Kvalsund boats remain under excavation

Wrecked or deliberately discarded remains

To this category belongs ships and boat remains found in bogs that have entered the records as a result of Natural and Cultural formation processes. A wrecked or abandoned vessel near a shoreline, river, or lake bank may gradually be covered by sediments and peat over time. Although they might appear similar to intentional ritual deposition, their positioning relative to the shoreline in antiquity, botanical analysis, and the lack of other cultural features usually associated with offering might help clarify the context.

The so-called Halsnøy boat (ca 400 AD, Kvinnherad municipality) and the Haugavik boat (1st or 2nd c. BC, Sømna municipality) might have entered the archaeological records in such a manner, as they have lain near the shoreline in antiquity.

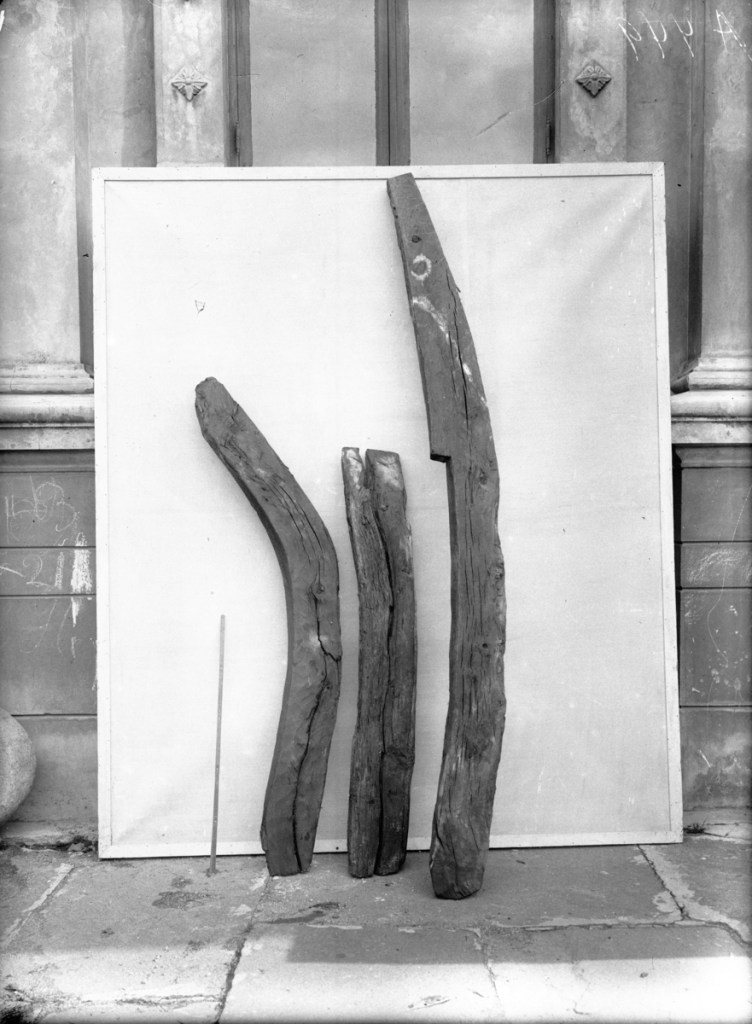

Wooden Blanks

This category is mainly made of finds of stems and keels (but not only) that are either partly finished or roughly shaped but, in both cases, laid into wetlands unused. When describing this category, Shetelig and Johannessen explained these finds as stemming from a practical context. Indeed, they reported that West-Norwegian boatbuilders still stored blanks for stems, keels, and frames by sinking them in water, preferably at sea, to better preserve the wood (Shetelig and Johannessen 53).

But why wooden blanks were deposited at sea or bog water?

The earliest mention of a similar practice is found outside Scandinavia in the 3rd century B.C. In the Argonautica, Apollonius Rhodius writes:

“And as when woodcutters cast in rows upon the beach long trees just hewn down by their axes, in order that, once sodden with brine, they may receive the strong bolts”

Translation by R.C. Seaton, 1912

Here, not blanks, but entire logs are kept at sea to soak before being worked. Water storage of timbers, employed today by the lumber industry to preserve a high volume of cut logs, helps reduce decomposition by preventing fungal and bacterial attacks. At the same time, it impacts the properties of the tree as well, rendering it permeable and dissolving extractives. The increased porosity makes the wood more susceptible to quicker drying and keener to absorb preservatives (Malan 79). Moreover, the leaching of starch and other foodstuffs minimise the possibility of insect attacks at a later stage (Malan 79). Another benefit from wet storage is that timbers might be less prone to distortion and splitting under work (Malan 79).

The actions of Apollonius’s woodcutters recalls the practice of water storage, not for the prolonged storage of the logs but more for the side effects connected with it, perhaps to avoid distortion and splitting.

The practice of water-storing logs is a practice also known in Norwa for traditional boat and shipbuilding. Godal (66) based on his craftsmen experience, describes the benefits of wood stored in water (both at sea or in bogs) as:

- Softer and easier to work;

- It tolerates more twisting and bending;

- More resistant to cracking compared with wood not kept in water;

- It dries faster.

Moreover, Godal (66) states that logs can be kept at sea for 2 years while in bogs for up to 10 years.

However, a log ain’t a wooden blank!

Wooden blanks are already worked and shaped or pre-shaped before they are put in water. As suggested by Sylvester (142), that is probably because of timber conversion technology employed by the boat builder known as “wet technology” (a term coined by Vadstrup).

All the way up to the early medieval period and probably later, working greenwood was the norm. There is a vast difference between working wet wood and dry wood with hand tools. The way tools “bite” into the wood and release shaves are entirely different. Hardwood like oak is soft to work when freshly felled, but it becomes harder after drying (Vadstrup 104). This is also reflected in the shipbuilding tools of the Viking Age, which are most effective in working freshly cut and water-stored wood (Vadstrup 111) Thus, after the trees were felled, they were worked right away or water-stored until before they were needed (Vadstrup 108).

Thus, wooden blanks may have been laid in water to keep the timber fresh for later use and acquire those benefits from the alterations happening during the water storage. The advantage of storing blanks in wetland areas vs at sea perhaps had to do with avoiding the risk of marine borer attacks. However, Godal (66) suggests that this is avoided by placing the timbers at the tidal range, which will leave the wood dry for a while and will create an unfavourable habitat for the eventual borer. On the other hand, bog water is rich in tannic acid, a potent preservative and biocide. Recent studies have indeed pointed out the benefit of tannins as a wood preservative (Silveira et al.; Tondi et al.). Perhaps, blanks were intentionally laid in bog water to also saturate the timbers with tannins which would have prolonged the resistance to organic attacks.

So, it might seem that the practice of lay blanks in a wetland is somehow strictly related to shipbuilding technology. However, Westerdahl (20) argues that some of these blanks found in bogs may have been ritually deposited as “pars pro toto sacrifices”.

“A reasonable intention could have been a ritual gift of a stem to the gods. Perhaps it was wood of the same tree as the stem that was used in the vessel about to be built.”

Westerdahl 20

Wetlands are liminal places where water and land coexist one into the other. It is not difficult to imagine that they played a sacral role also in boatbuilding, to create an object that stays in the “between”. However, both explanatory models may have existed side by side, as suggested by Sylvester (143).

Literature

Crumlin-Pedersen, Ole. ‘The Boats and Ships of the Angles and Jutes’. Maritime Celts, Frisians, and Saxons: Papers Presented to a Conference at Oxford in November 1988, edited by Sean McGrail, Council for British Archaeology, 1990, pp. 98–116.

Godal, Jon Bojer. Tre til båtar. Landbruksforl., 2001.

Kaul, Flemming. ‘The Bog – The Gateway to Another World’. The Spoils of Victory: The North in the Shadow of the Roman Empire., edited by Lars Jørgensen et al., Nationalmuseet, 2003, pp. 18–43.

Malan, F. S. ‘Some Notes on the Effect of Wet-Storage on Timber’. Southern African Forestry Journal, vol. 202, no. 1, Taylor & Francis, Nov. 2004, pp. 77–82.

Nordeide, Sæbjørg Walaker, et al. ‘At the Threshold of the Viking Age: New Dendrochronological Dates for the Kvalsund Ship and Boat Bog Offerings (Norway)’. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, vol. 29, Feb. 2020, p. 102-192.

Shetelig, Haakon, and Fr. Johannessen. ‘Kvalsundfundet og andre norske myrfund av fartøier’, Bergens museum, 1929. National Library of Norway,

Silveira, Amanda G. Da, et al. ‘Tannic Extract Potential as Natural Wood Preservative of Acacia Mearnsii’. Anais Da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, vol. 89, Academia Brasileira de Ciências, Dec. 2017, pp. 3031–38.

Sylvester, Morten. ‘Finnemoen i Nærøy – En Båtkjøl Og et Batverft Fra Merovingertid?’ Viking, vol. 72, 2009, pp. 137–78.

Tondi, G., et al. ‘Surface Properties of Tannin Treated Wood during Natural and Artificial Weathering’. International Wood Products Journal, vol. 4, no. 3, Taylor & Francis, Aug. 2013, pp. 150–57.

Vadstrup, Søren. ‘Den Våde Træteknologi’. Træskibs Sammenslutningens Årbog, 1992.

—. ‘Vikingernes Skibsbygningsværktøj’. Årbog / Handels- Og Søfartsmuseet På Kronborg, vol. 53, 1994, pp. 100–23.

Westerdahl, Christer. ‘Boats Apart. Building and Equipping an Iron-Age and Early-Medieval Ship in Northern Europe.’ International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, vol. 37, no. 1, 2008, pp. 17–31.